Email, pleasure, and one-sentence perversions

Miłosz Wojtyna14 lipca 2023

How to write better emails – and enjoy work more? How not to sound robotic – and take care of those we write for instead? How to get productively radical in this most mundane activity of all? Here’s our perverted answer.

Disclaimer: We’re not hippie. But in our sense-oriented research on communication we have found that empathy and relative intimacy are super useful – and perhaps more productive than formulaic professionalism. And that’s why… this.

What’s the difference between love letters and your work emails? Let’s compare them for the sake of experiment: these two genres. How is writing to your lover different from writing to your customer, supervisor, or team member? How are your ambitions and goals different in these two realities – the realities of intimacy and professionalism? Is there a difference at all? How could work be different if we actually loved the people and the job – and were loved back? You know, romantically and all. How would communication at work be organised?

Let’s imagine an email exchange like no other, like all other.

Yes. All of this sounds like something that could never happen, never be sent, never be openly done – unless in “The Bold and the Beautiful”, or perhaps an epistolary novel that imitates the flourish and ornamentation of 18th century popular fiction. It is too much. Love letters at work are too much.

There is something to them, though. Don’t you think? The excess makes you frown at style, but also wonder how it might feel to be the addressee of an email like that. To be celebrated. To receive a message in which you learn about someone else’s intention to care about you. Yes, there’s that focus on “you”. That clear assurance that somebody’s entire attention is most clearly on us. The undivided attention. The unwavering determination. The “yours forever”. Wow. At last, a bit of empathy in this narcissistic world. Something that every narcissist wants – others to stop self-scrutiny and look at them.

“Yours forever”. Wow!

Fun, huh? A bit of luuuv, and things go crazy!

And now think about the emails you write and receive at work. Stuff like this is perhaps the best that could happen:

Fun, eh? And these are rather well-written messages. They focus on the matter, they are kind, clear, and relatively brief. Go for that style, and you will never walk alone! People will reply willingly, and you will be respected all around. I’m quite sure of that.

Unfortunately, you have seen worse, haven’t you? You have received messages – you do, every day! – that are chaotic, hectic, over-informative, under-informative, incorrect, incomprehensible, or hurried. Yes, hurry is a major problem – so much of what we write and read is created under radical time-pressure and bears a birthmark of obligation. You can see quite often – in the style of the email – that the person who wrote it didn’t enjoy the process at all – and was pressed (internally or externally) to do it. That is quite common for work emails, and perhaps less common in love letters.

—

There’s a gigantic difference between these two types of messages: not only between the emotions and proximity of love as opposed to the intended rationality and formality of work, but also in how much we enjoy writing in both of these contexts. We often do in our private lives. We text, email, and chat here and there on all devices. Somehow, though, we often don’t enjoy writing in our professional lives. But we are still obliged to do it. And very often we do it rather well.

There are many reasons why this comparison seems radical, or perhaps quite stupid. We are comparing very different realities. But it is my intention – or, I should say – it is our intention, because I am writing on behalf of myself and my wife, my regular romantic-professional correspondent – to suggest that it makes sense to bring a bit of love into that world of work. Why?

Why? Because there’s too much pain.

One reason is that there isn’t enough pleasure at work. There isn’t enough satisfaction – and there is too much pain. There is pressure, there is scrutiny, there are limitations, power and deadlines. Always. Whether you work in development, sales, HR, finance, or management. There’s pain, for sure, on the way to gain.

Emails, for instance, are hardly ever a source of pleasure. Information and frustration – yes, these they bring more often. But pleasure? When do they give us that? I can imagine the following conditions: emails give us pleasure when and only when they contain praise, good news, make things easier – or are extremely easy for us to process. This is just about the degree to which your everyday writing at work might be pleasant to you or anyone. That’s not too good, nor too bad either. It’s the prose of life, not a love story.

But there are situations.

Situations at work in which you want to act in a special manner: to contribute more and to get more. You want to reduce the distance, melt the ice, cut the bullshit.

It’s difficult to know for certain that a given moment qualifies as such a breakthrough situation. The mundane reality of repetitious activities stops us from realising, sometimes, that these scarce moments (of clarity, of brilliance, of focus) decide about the totality of our lives. At these moments, you need all the resources that are available, all the lucidity of mind, clarity of thought, power of language. You need something special.

We want to give you that something. We want to bring to you a single useful piece of advice that you will never find in guru blogs, nor in your consultation with ChatGPT (you might discover this yourselves, though!). Something super easy on the one hand and very, very human on the other. We will explain in a moment how to write powerfully with the help of one simple strategy – and we will try to write your important emails together.

—

We will first take a detour, though, to summarise the basics of email writing – all the things that we think you know how to handle very well. We will try and show that all the basics are a good starting point for writing standard, decent emails – and something that you want to rely on to keep afloat. But if you want to navigate deeper waters – make impact, push your ideas into the world, enjoy your work more – you might wish to do something else.

For powerful writing, powerful strategies are needed.

More powerful than what? Let’s revise these basic tips and tricks. I am shaking a bit here, because they are the drama of everyday work: we know these tips, rules, and methods, but sometimes fail to follow them not because we don’t know how, but because we don’t know when. We often don’t have time. And that’s perhaps the most terrorising reason why the quality of our emailing (or of communication, in general) is, well… subprime. We are pressed and pushed, and hardly manage to devote enough time to things that are only done well if they are done in an unhurried manner (Can you see me preaching mindfulness and slow thinking here? I most likely am). And then we search for quick solutions – and easy ways out. But if you treat your brain seriously, there are no such ways.

But there are gurus and their advice – partly useful, partly distracting. With emails, that’s exactly the case: you can read about better emailing everywhere online. You can read about the necessity and importance of:

- following email etiquette,

- writing clearly and concisely,

- starting with a clear subject line,

- checking for punctuation and spelling,

- starting with a strong sentence,

- starting with BLUF (bottom line up front),

- using functional tags[1],

- using a CTA at the end,

- changing ridiculous reply-reply-reply-reply-reply subject lines (Re: Re: Re: Re:),

- being polite,

- removing passive voice,

- writing one topic per email,

- removing qualifiers and hedging (“If I may say so, I would like to stress that I would by all means be interested in knowing what you think about…” and stuff),

- proofreading,

- adjusting your tone (what does that even mean?!),

- using bullet-points or check lists,

- using emphasis (bold, italics, underscore),

- adding lines of space,

- compressing attachments,

- adding attachments,

- sending at the right time,

- showing rather than telling,

- adding emojis reasonably, and of

- installing tools at your device that will help you automate some of all that.

Plenty of advice. Yes, regular everyday emails need all that.

Yes, regular everyday emails need all that. Follow these strategies nicely, and you’re going to be just fine. If you want to see how they work in practice, you can download the basic guidelines our team have prepared. But you know how to handle such recommendations, don’t you? And if you have time, you follow the advice and do all these things. If you have time.

Let’s have a look at one such piece of advice coming from an email guru. “Write in the subject line what is required of the recipient”. That’s a good one. And a common one, too. Everyone will tell you that you need to write in that subject line what is needed of the recipient. What they are supposed to do. What action is required. How they are supposed to respond. So that they do what you want them to do. And quickly. Preferably, with no hesitation. As if they were automatons.

And while that is, indeed, the best thing to do in a hectic environment in which information overload is immense and deadlines short (which is: everywhere), you might choose a different strategy if you want actual attention rather than just a quick act. Because gurus are wrong when they claim that the thing all your bosses want the most is pure information and data. What they want the most, instead, is peace of mind. And a certainty that you are handling business well. Your peers want the same. Their emails are as numerous as yours, they multitask, too, and the most joyful thing you could write them is this: “All things sorted. No attention required”. That’s what we dream of: a reality of work in which pleasure results from peace and control.

The best email ever: “All things sorted. No attention required”.

If you are communicating something important, you can use two strategies: either go for the smoothest experience, or rely on the extreme. With the first strategy in mind, you want to write an email that is as unobtrusive as possible. Simple, short, brief, no ornament, no mumbo jumbo, no excessive socialising, no detours. Facts, information. Lucid and lite. Something your reader could consume easily and move on. All the advice listed above will help you write exactly like that. And if you send dozens such emails every week, people will appreciate the fact that the messages are easy to process and don’t require much time to read and understand. This strategy pays off very well in long-term relationships. This first strategy – let’s call it “decent writing” – is very good on daily basis because it saves the precious brainpower of people around. And, as you very well know, brains are a scarce resource. It’s nice to respect them. Writing adequately is a nice gesture of care. A nice gesture of love.

Let’s try and practice this strategy with an email you want to – or have to – write right now. Spend some 10 minutes writing that important email of yours, making sure it’s really good.

Done? Good. This is decent, indeed.

But if you want something different – because this time your business is not about systematic consistency, but about disruption (a new idea, a critique, a challenging proposal, a request for change, a big “thank you”, etc.) – you want people to slow down and notice. Instead of giving them something easy, you want to send them an email that is “positively difficult”: something that requires a bit more attention. You want the readers to return to their mailbox and think: “Wow, this is something strong!”. This second strategy will slow them down, sure. But for a reason. We will call the strategy “powerful writing”.

What is it all about? Deautomatisation. Derobotisation. Defamiliarisation. De… what? All of these mean the same: powerful writing consists in the breaking of rules. In writing like a human who loves rather than like a robot who has to.

We’re not robots. Why do we write as if we were, then?

You may say: “Breaking rules? That’s against professionalism!”. Professionalism! Yeah. The Holy Grail of wannabes. Of everybody who wants to toe the line while those who know rules really well will make quicker progress and enjoy freedom without – or against – the code of conduct and etiquette. Nasty? Yeah. But think about “the best performers” (ugly name!) you know. Many of them will often negotiate their way around rules for the best solutions because they know rules are designed to maintain stability and the status quo. And they seek something else: success and change. That’s why they will write messages about things nobody else has written. They will say thank you when nobody does. They will ask questions smarter than anyone. They will reply in a more detailed way. They will read more carefully. They will understand better. Because they have discovered the benefits of smart radicalism.

This strategy is so much fun – specifically because it imitates the flamboyance and flourish of love letters with the aim of persuading the reader that “yours truly” is capable of being in control of the world as much as she is capable of controlling the written text. If you write like you love – with all your heart and brainpower – the world will notice.

Disruption loves danger.

There are numerous ways of doing this – of putting this strategy into life. You’re going to hate most of them, because they’re radical and dangerous (disruption loves danger!). So here come 7 examples of what you can do (and illustrations that show you how that’s done):

- use repetition or parallelism,

- paraphrase what you’ve written already,

- give examples,

- make sure there are more of “you” than of “I”,

- call after you’ve clicked “send”,

- ingratiate yourself,

- don’t show you are in a hurry – or don’t hurry.

Most of these can be effectively used with one simple technique. What technique is it? Watch me now: to make your decent writing powerful, add one sentence. Just one sentence that repeats, paraphrases, illustrates, presents gratitude, or shows you have time. That one sentence is something that can improve a decent email the way love improves friendship.

How can you do that? Let’s have a look at some examples of emails that are just fine – and see how we can tweak them with that single additional sentence. Let’s call them “one-sentence perversions”. They are perversions, because they are departures from the norm: normally, they’re not even there.

Let’s have a look at some examples.

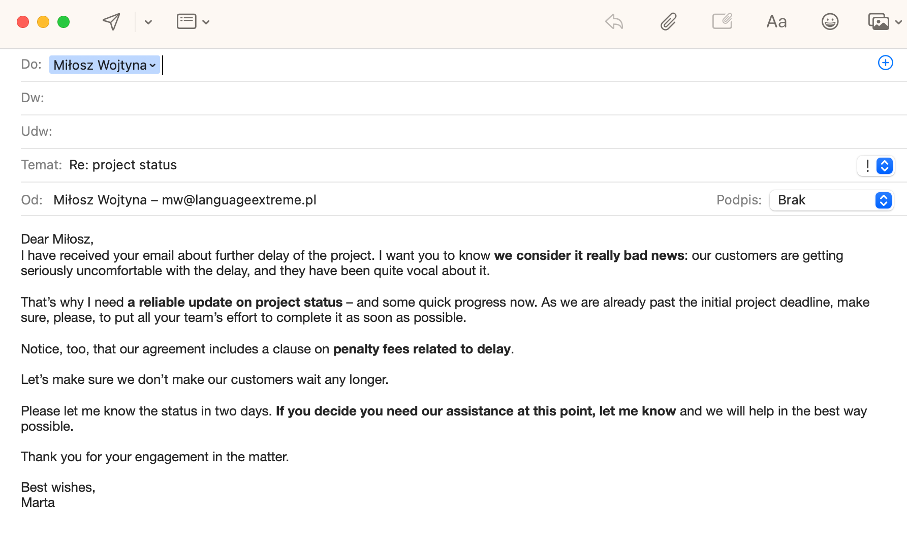

In the first email, Marta (a fictional person) reminds a fictional Miłosz rather powerfully that the delay in the project Miłosz’s team is supposed to deliver has become a major problem. She does so in a way that doesn’t leave space for doubt (Miłosz will not wonder any more if it is a serious matter already or not), but offers a polite gesture of solidarity that helps both parties maintain some dignity and readiness for further effort (“If you decide you need our assistance at this point, let me know and we will help in the best way possible”). The email is longer and more empathetic than it perhaps could – and it contains some tiny perversions that show care and engagement. They’re those bits of love that we want you to use in your writing.

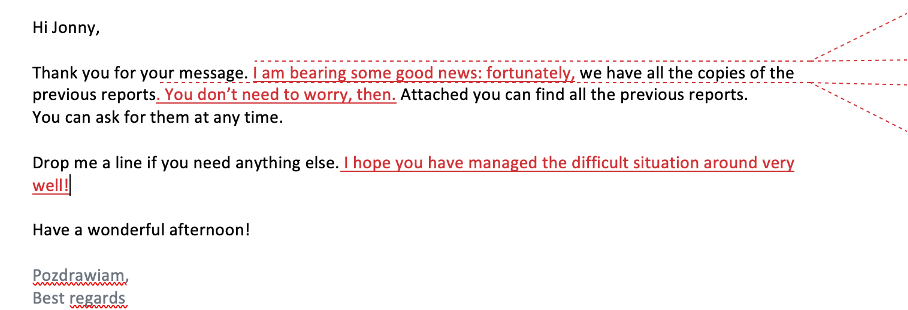

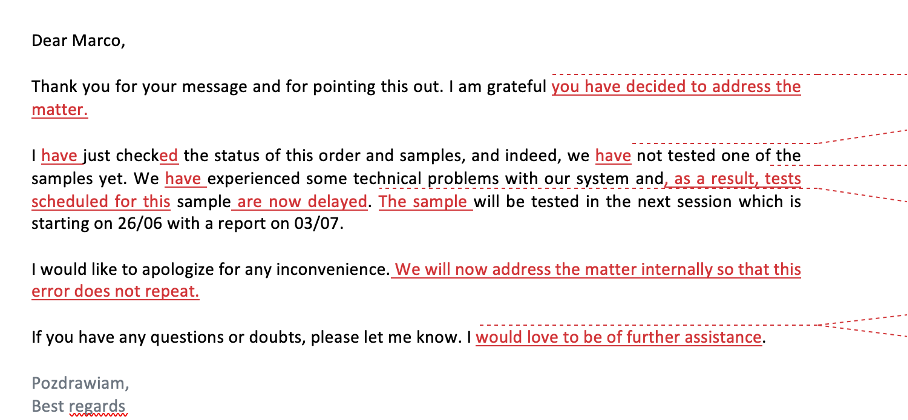

In the second example, one of the participants of our workshops replies to a request from their own customer. The request refers to some troublesome situation the customer is in, and seems rather urgent. No wonder, then, that our participant, an excellent customer service specialist, replied super quickly, providing the customer with the relevant data. Have a look at the original exchange, though, and observe how the edited version differs. Notice the additional sentences that – though entirely optional – add a caring quality to the message. This is what we mean by those tiny one-sentence perversions everybody can afford in their writing: a bit of care and compassion. (Wow, we sound like a love-and-peace sect already!).

Our third example is a real email one of our customers wrote in our training – and then edited it before sending it to an actual person at work. Can you notice how the first and second versions differ only in the tiny passages marked in red? This is where that additional bit of engagement is signalled – the stuff that doesn’t have to be there but is there for a more pleasant experience of both the sender and the recipient. Fun, huh?

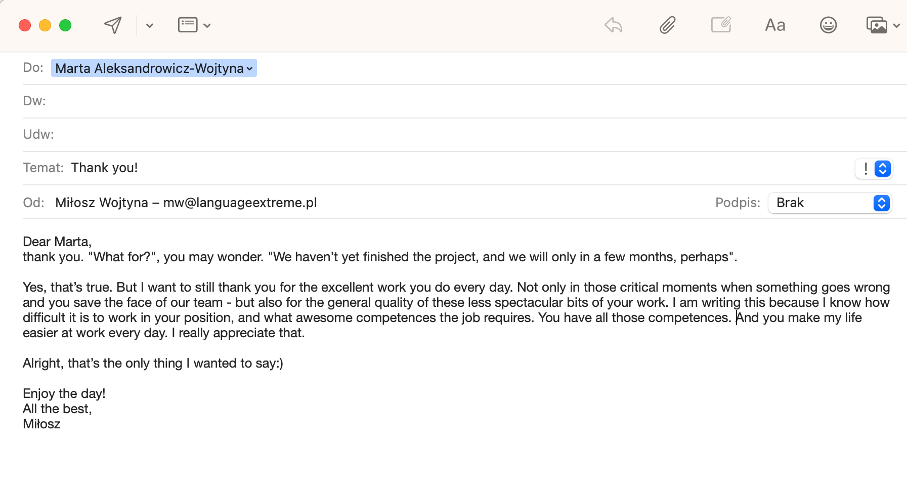

In our fourth example – which also takes inspiration from love letters, Miłosz writes to Marta without an operational reason. Without an evident pragmatic motivation. He says “thank you” – not really because he has to (because a project has finished, or because he has just signed a major contract with her), but because he wants to. This email is a bit more flamboyant – and sweet – and some of you might find it too excessive. Why? Perhaps because such unsolicited gratitude is the rarest thing we do in our work correspondence. And, we admit, an email like this will most likely be seen as weird. But if you don’t make it too cringy, it will go a long way.

—

It’s now time to test the second strategy of “powerful writing”. Add that one sentence to your original message. One more sentence.

Ready? Done it?

Remember this, too: you will only be able to add that one more sentence if you economise effectively in the other parts of that message you’ve written. Save space to use space.

—

This is our advice of the day, then: decide what you want to achieve, and then follow one of these two strategies. If you want systematic progress and long-term good performance, just write that “decent” email every day – a good one, one that complies with all the rules. That’s not too easy, but not too difficult.

But when you are ready for disruption – for that breakthrough – choose the “powerful writing” strategy for this important message that you want to matter, and add something to the decent standard that goes beyond and above. One sentence that makes the email stronger, more extreme, or even weird. It’s risky, sure. Above all, though, make sure your emails bring a bit of that alien quality to work – a bit of pleasure – for you, and those you write for.

Enjoy being human, you lovely people!

[1] For instance, FYI: For your information (read-only), ACTION: for emails that need attention, URGENT: High priority emails, APPROVE: Emails with actions that require authorization. Source: https://www.accountmanager.tips/30-ways-to-write-better-emails/